RESEARCH

AN EMOTIONAL PROCESSING MODEL FOR COUNSELLING AND PSYCHOTHERAPY, A WAY FORWARD?

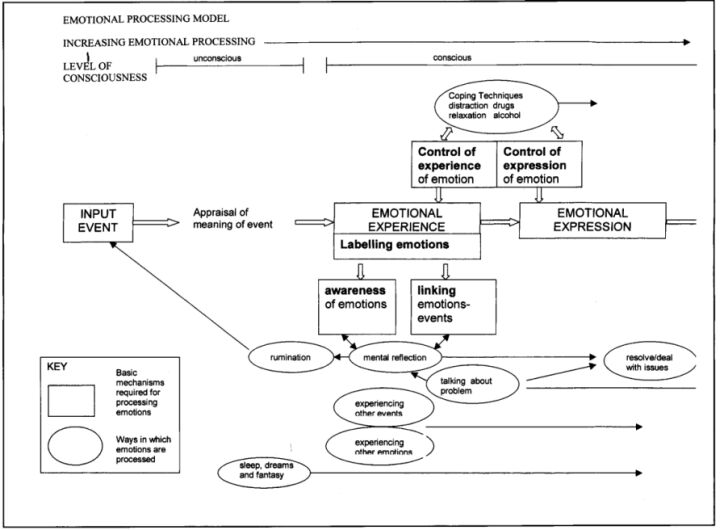

The Model

We wanted to develop a theoretical model to be useful in both the assessment and counselling of clients. Most individuals when faced with stressful, negative or adverse events in life successfully “emotionally process” these events in such a way that they do not intrude, persist or impinge on their daily life. They achieve this by (1) expressing feelings, (2) talking about issues, thinking about them and reaching conclusions (3) changing life circumstances which lead to the distress (4) dreaming or daydreaming, (5) getting involved in other activities, (6) experiencing other emotions, and (7) use of alcohol or drugs. However, if the individual fails to process events (such as trying to suppress any negative emotional experience) we thought it might make it hard for them to deal with or reduce the emotional impact of the event. This might not matter for the smaller, everyday negative events, but if more serious traumas, stress or abuse should occur, then failure to process these emotional events could have serious consequences.

We tried to identify the crucial emotional processing mechanisms which are necessary for successful emotional processing.

The accompanying diagram shows how we have tried to conceptualise the stages in experiencing and expressing an emotion. It suggests how the emotional experience is related to other mental events and what the conditions are for satisfactory emotional processing. The arrows suggest how the different processes interact with each other.

Input

Emotions start with an event, usually an interpersonal event. This may be a small discrete event such as severe criticism or ongoing conditions like stressful work environments or major traumatic events. It can also refer to memories or thoughts about an event which can also invoke emotion. For this to happen the event needs to be consciously or unconsciously ‘registered’ by the person. If the event was not even unconsciously detected by the person (like a blind person failing to see an object in front of them) no emotion would be experienced at any point within the person’s psyche. However, an unconscious, rapid and extremely complex appraisal of the meaning of the event is usually made by the person based on past memory and experience and the cognitive developmental level of the person. For instance, someone who has previously been criticised and has come to expect rejection from others may unconsciously ‘read’ someone’s words as critical and will respond by feeling hurt. Problems that can occur include the failure to register and respond to important events, or interpersonal cues, a block in feeling emotions, or feeling too much emotion because of exaggerated input like a person with paranoid constructs who sees slights and threats in innocent remarks and gestures.

Emotional Experience

We believe the emotional event and the meaning the person attributes to that event determines the type of emotion experienced. The emotion itself involves physical reactions and sensations and is also experienced psychologically. Frijda (1988) has suggested that emotions consist of a few fixed patterns of physiological reactions which are switched on as a package but each person has a complex way of viewing the world and will unconsciously understand events in their own unique way. The psychological experience of the emotion will depend critically not so much on the physiological reactions engendered but more on how the person has interpreted the event.

Problems of Control

Problems of control of the emotional experience could mean that although the emotional event is initially ‘registered’ (consciously or unconsciously) the experience is aborted, suppressed or constricted. This in turn inhibits emotional processing and can lead to unrelieved tension, panic attacks and dysfunctional attempts to control feelings, such as over-use of alcohol and drugs. The degree to which the person allows themselves to experience an emotion will be affected by their attitude to having emotions. For instance there may be certain family or community rules such as ‘men don’t cry’ which may cause individuals to stifle the experience of emotion as soon as they begin. The individual may also be afraid of experiencing emotions (as in panic disorder) and so has learned to suppress angry, fearful or depressed feelings.

Labelling

Automatically and usually unconsciously, individuals feel the emotion as a psychological whole and ‘label’ the psychological state. Some individuals however are unable to label such an emotion at this psychological level and instead experience it as a set of physical reactions or sensations; so instead of experiencing ‘anger’ they label it as ‘going red in the face’, trembling or feeling faint. Individuals widely differ in the way they can accurately label their emotions but generally we would expect these skills to improve during their development and upbringing and they are moulded for instance by gender expectations.

Linkage

Linking the emotions that individuals feel with the events which cause the felt emotions may be consciously or unconsciously achieved. It may be done appropriately (‘the boss is criticising me’) or inappropriately (‘it was something I ate this morning’) or the person may be just not good at linking events to emotions. We believe that correct linkage depends on the person’s ability to label their emotions. If the person is poor at labelling, it is unlikely that they will then be able to accurately link an event with the emotions they feel.

Awareness

This describes the degree to which the person is consciously aware of their emotions or the physical sensations that make up the felt emotion. Problems occur if individuals are hyper-aware of increased heart rate, choking sensations or difficulties in breathing and ruminate on these rather than their psychological emotional state. Patients with panic attacks or hypochondriasis are usually hyper-aware of bodily sensations. However awareness of one’s emotional state is not a prerequisite for successful emotional processing because much emotional processing occurs unconsciously.

Emotional Expression

This describes how the person gives bodily expression to their emotional experience. In practice it is closely tied to the emotional experience and may occur almost simultaneously, for instance sad feelings and crying usually occur together. Emotions can be expressed directly and immediately, such as (1) shouting at someone who has let you down at work or who has upset you in some way (2) directly but more tactfully, such as trying to deal with the reasons why they let you down (3) by talking to others about your feelings or writing down your experiences. Indirect expression of emotion include the proverbial kicking the cat or generally directing emotional expression at unrelated people, or things. Individuals will have developed familial or cultural attitudes towards the expression of emotion which also need to be understood.

It is also quite possible to experience emotions very strongly without expressing them by word or action to others.

Blocks in the System

Problems can emerge if there is some deficit or blockage in any of these processes. Different problems occur depending on the nature of the deficit or blockage. For instance, failure to label emotions correctly may result in confusion about one’s experiences; suppression of the experience may lead to tension; failure to input events properly may produce emotional blankness. If a therapist could identify where the emotional processing deficit lay, it would provide direction for the counselling and psychological therapy.

Case Example :

The following case example provides a practical illustration of how these concepts might be used during therapy.

A 28 year old woman was referred to me for psychological therapy by her GP with ‘a history of stress related symptoms and depressive illness’. She had previously responded to antidepressant medication but low mood and an inability to satisfactorily cope with work continued. I used a combination of psychotherapy in which patterns of childhood upbringing were explored and linked to current behaviour and attitudes and cognitive therapy, based on her current way of interpreting her own actions and those of others. As part of my approach the patient was invited to fill in our Emotional Processing Scale. This suggested that she experienced both strong positive and negative emotions and was in many respects emotionally healthy. However, the assessment showed that she failed to link correctly emotions with triggering events.

We explored this in the therapy session and it became clear to the patient that there was a pattern in which she would typically experience strong emotions, particularly sadness, but which she failed to connect with events such as being ignored or blamed by her family. In the absence of any such associations the patient had assumed she was ‘a depressive’ with a hereditary biological weakness which periodically caused depression. Further therapy involved exploring the links between ‘mysterious’ bouts of depression and the emotional events triggering the bouts which helped the patient realise that strong emotions do not emerge ‘out of the blue’ for no reason. She then realised that her self concept of being ‘a depressive’ was unsustainable and she took on a much more positive way of seeing herself. Not only did she feel greatly relieved by this realisation but she went on to develop a new way of understanding which prevented ‘depressive breakdown’ in the future. Sadness was regarded as the natural and normal consequence of difficult life events, as opposed to deficiency or illness. The use of the Emotional Processing Scale was a useful adjunct to both psychotherapy and cognitive therapy and was entirely congruent with both.