Helen Bolderston

Consultant Clinical Psychologist

Dorset HealthCare NHS Trust

Much of the literature about processing emotions focuses on supposedly negative or difficult emotions, such as anger and anxiety. There seems to be an assumption that we can all process so- called positive emotions in a straightforward way, something which does not match my own experiences, or my observations of my clients. Indeed, Linnehan (1993) described her patients with Borderline Personality Disorder as ‘emotionally phobic’, equally avoidant of pleasant and unpleasant emotions.

Gestalt theorizing about our experiencing of emotions has a much broader focus of interest than just ‘negative’ emotions; it particularly focuses on how we each differ in our style of ‘being’ or living our emotions (feeling them, expressing them, processing them). No distinction is made between ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ emotions; all emotions are seen as fundamental parts of our lives, and as such are potentially growthful and useful, if not always pleasant. There is a similar view of emotions in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes et al 2003), where the ‘negativeness’ of certain emotions is seen as a result of their being evaluated as being so, because of the kinds of circumstances they typically occur in, rather than any inherent ‘badness’.

Gestalt Cycle of Experience

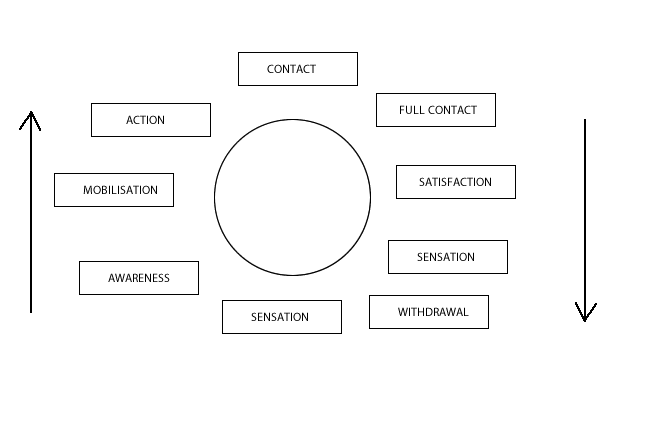

As a humanistic psychotherapy, Gestalt is as focussed on ‘healthy’ functioning as it is on psychopathology. The Gestalt view is that well functioning humans experience an uninterrupted flow of experience, characterised by the rising, satisfying and then fading again of needs, emotions, physical sensations and so on, without the individual unnecessarily disrupting this process. This ebbing and flowing of energy is usually conceptualised as a ‘cycle of experience’ (sometimes known as the ‘contact-withdrawal cycle’)(Perls et al (1951/1973), Clarkson (1989)).

The Gestalt view is that to process any emotion fully and healthily, we need to pass round the cycle of experience, moving up the left hand side, becoming gradually more and more energized and mobilized as we move from the very first sensations to full contact with the emotion, which is a rich (although not necessarily pleasant), whole organism experience (including cognitions, bodily sensations, felt emotions etc). Only when this happens, will energy start to drain away from this particular experience or cycle, as we move down the right hand side of the cycle towards withdrawal and the creative void.

One example would be the rising excitement felt as a reaction to our team scoring a goal in a football match, perhaps peaking (full contact) with us shouting, laughing and jumping out of our seats and then subsiding as the match continues, with new and different cycles beginning, depending on what happens next in the match and around us.

Another example would be the rising distress and grief we might feel as we have memories of a loved one who has recently died. Energy might be mobilized to a point where we sob, cover our face with our hands, cry out their name and so on. After some time at ‘full contact’ the energy will start to subside, we might quieten, be able to think more calmly about what has happened, and at some point be ‘available’ for other experiences; in Gestalt terms, for other figures to emerge from the ground.

Of course, in reality, cycles do not arise one at a time. We are all engaged in hundreds of cycles of experience at any one time, some relatively quick to move round (I’ve just noticed I’m thirsty, so I get up, go to the kitchen and drink water until I’m no longer thirsty), others much longer term (pregnancy would be one example). Also, in Gestalt, these cycles are clearly not only a way to conceptualise our emotional experiences, but rather a way to conceptualise how humans spontaneously regulate themselves to meet all their needs and thus to function well in their environment.

However, it is often the case that we do not move freely around the cycle of experience and fully experience emotions; we have all to a greater or lesser extent developed ways in which we inhibit straightforward emotional experience.

Styles of Contact

Gestaltists recognise that in reality we often do not move round the cycle of experience in a smooth and uninterrupted way. Instead, we each have a unique pattern of ways in which we interrupt and inhibit our move towards and later away from full contact with emotions. These used to be known as interruptions to contact, but are now more usually referred to as styles of contact, to acknowledge the fact that these ways of being emotional (or not) are not in themselves negative

Gestaltists recognise a whole range of ways in which we inhibit our energetic flow around emotions. The most commonly identified ones are:

Desensitization – I do not even begin to experience something, such as an emotion

Deflection – I take my awareness away from the emotion

Introjection – I use an introjected rule or opinion to inhibit myself e.g. ‘It’s weak to have emotions’, ‘I won’t be able to cope if I let myself feel this’

Projection – I see in others emotions that I deem unacceptable, but do not recognise them as part of my own experience

Retroflection – I turn back in on myself emotions (e.g. anger) which actually need to be expressed to others, but which seems too difficult or frightening or unacceptable

Spectatoring (also known as egotism) – I constantly block spontaneity of experience by running an internal commentary about my experience of an emotion, rather than fully experiencing it.

Confluence – I over identify with an emotion, seeing it as all I am, and so am unable to separate from it and let it subside. This might also be a way in which I avoid moving into the ‘void’ part of the cycle, which in itself might be enormously frightening to me.

We all moderate our experiences of emotions to a greater or lesser extent (MacKewn 1996); Gestaltists see emotional processing on a continuum rather than in a binary, good/bad way. The issues that particularly interest Gestaltists are how fixed or stuck are we in a particular way of moderating emotional experience (eg always telling ourselves that it’s weak to feel upset) and how fixed are we in how fully or not we let ourselves experience emotions (eg do I always stop myself feeling anger before the urge to shout gets ‘too’ strong?) Also, am I aware of these styles of moderating my emotional experiences and more than that, are they choices or a compulsion?

As an example, it may be that I have a particular range of ways in which I interrupt my passage round the cycle of experience with happiness. I may have learned to not notice the early physical changes associated with this emotion, I may have some introjections linked with my family history such as ‘my Mum has been unhappy all her life; it’s disloyal of me to be happy’ which might lead me to de-mobilize any energy that feels like happiness, or I may constantly monitor my emotional state, asking myself ‘is this happiness, am I as happy as I should be, as other people look?’ and in doing so interrupt my direct experiencing of the emotion.

Various Gestaltists have hypothesized about the possibility of particular patterns of interruptions or disturbance to the experience cycle being evident for different psychological problems. For example, Melnick and Nevis (1997) viewed PTSD symptomology as the result of problems with de-mobilization; disturbance in the satisfaction/ withdrawal part of the cycle.

Awareness, Acceptance and Change

Gestalt is an approach focussed on awareness. That is, a Gestalt psychotherapist will be working to try and help the client become more aware of themselves, their own particular style and patterns of relating, feeling, not feeling and so on. With this raised awareness comes choice; to carry on as I am (for example, deflecting my attention from sadness with jokes), or to experiment with being emotional in a different way. If I continue to use my old pattern of managing emotions (and so not fully processing them), this is an active choice, made in awareness. If I decide to try to do things differently, then my therapist and I may devise ‘experiments’ with the aim of me having a new and different experience with this particular emotion and my way of moderating my experience of it. The intensity or difficulty of the experiment is carefully calibrated so that I do experience something new (eg allow myself to feel some of the anger I have not expressed for the last 30 years), without the experience being so intense that I am overwhelmed and have a frightening or traumatising experience that I can not make use of therapeutically. Such experiments are often forms of behavioural exposure work (although Gestaltists do not tend to use those terms), but may take many other forms. Gestalt therapy is not focussed on a specific set of techniques; Gestalt therapy is more focussed on process.

In 1970 Beisser articulated what he called the ‘Paradoxical Theory of Change’. In simple terms this states ‘change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not’. So in the area of emotional processing, our task is to try and accept and allow our emotions, however difficult we or others find them. In being prepared to fully live our emotions as they are in this moment, change becomes possible. By ‘allowing’ and welcoming our emotions, by definition our relationship with them changes. It may or may not also be the case that the intensity and ‘flavour’ of the emotion changes. In this approach Gestalt pre-dates more recent, acceptance orientated therapies such as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

I would like to thank Liz Kerry and Laurence Hegan for the helpful discussions we had when I was trying to plan this article.